Even in my adult years, I still associate a library with a place you pick out books and get shushed for being too noisy — so I was surprised to learn that Toronto offers 3D printing services at 10 of its local branches.

Each branch oversees a Digital Innovation Hub (DIH) where Toronto Public Library cardholders can access a 3D printer — as well as other professional design and video production services — at little to no cost.

Residents can either take a certification course where they learn how to design their own prints using Tinkercad software, or they can select a pre-made object from the online Thingiverse catalogue which can be altered and customized with the guidance of library staff.

The prints themselves are all made of a plastic filament. The DIH purchases their own filament rolls and provides the material for library users at 15 cents per gram used.

Last Wednesday, I stopped by the Toronto Reference Library near Bloor and Yonge where staff members walked me through the 3D printing procedure.

‘Heart’ of the process

Before I headed to the downtown branch, I first needed a Toronto Public Library card. Once I was registered, I could reserve one of their printers three days in advance.

Rather than take a certification course to learn how to make my own 3D print, I decided to browse the online catalogue for an item that might pique my interest. I went into the project thinking I’d select a practical item that I could actually use.

That was until I discovered ‘Heartosaur’ — a Valentine’s Brontosaurus.

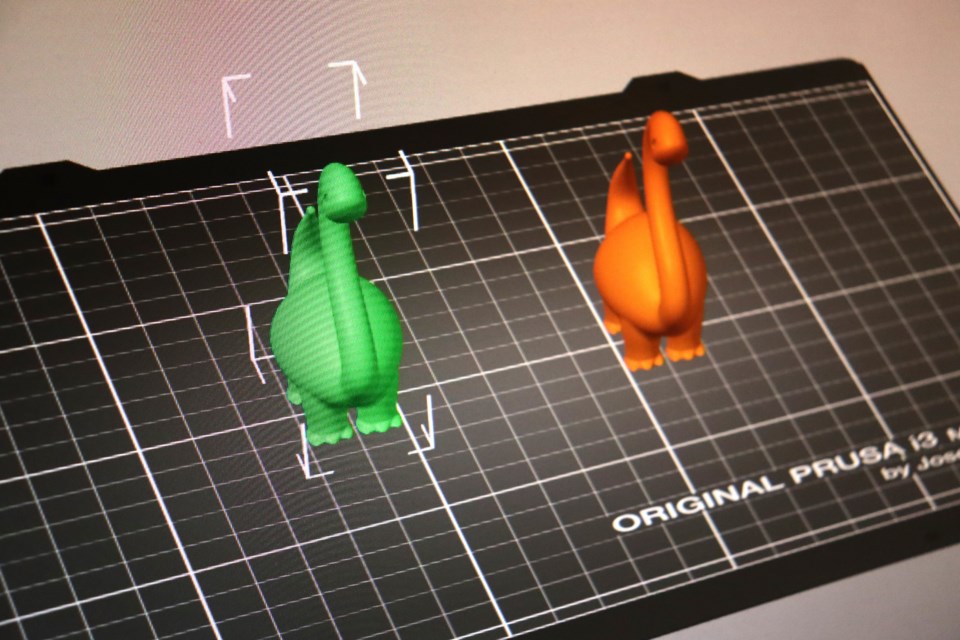

The design featured two identical dinosaurs facing one another in the shape of a heart. It was far too cute to ignore, so I was sold.

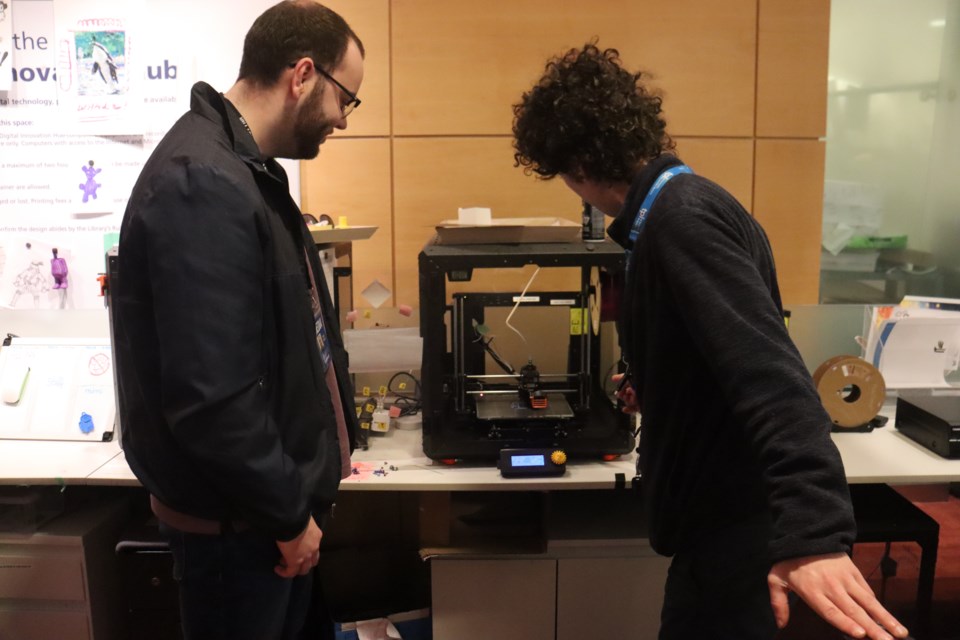

I headed to the Toronto Reference Library on Wednesday where I provided staff with the website link to the print. Alternatively, users can bring their design on a USB. Either way, staff will download and pull up the file on their computer and guide users through the final stages of the editing process.

Yamandu Sztainbok, one of the digital design technicians with the library, helped me modify some of Heartosaur’s specs using their 3D printing software PrusaSlicer.

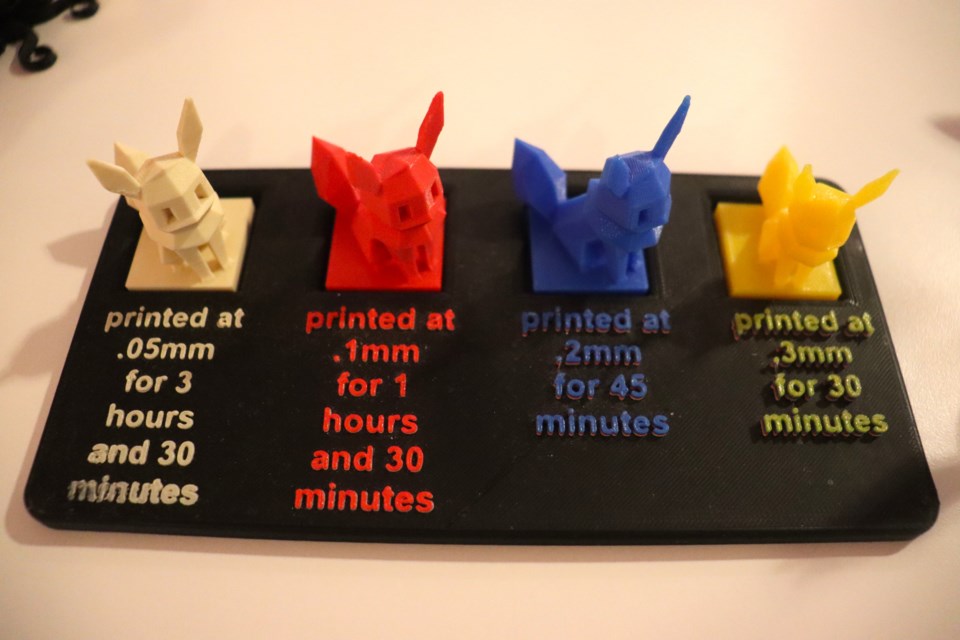

While the design was already preloaded from Thingiverse, he wanted to make sure I was happy with the size, resolution, colour and type of filler used to create Heartosaur. Those decisions would directly impact how long the print takes (If the dinosaurs are larger and have a higher resolution, the printing would be a lengthier process).

Sztainbok, who runs several classes each month at the library, added some support beams to the design so the dinosaurs’ necks would stay in place during the printing process. They would later be snipped off by staff after the print was complete.

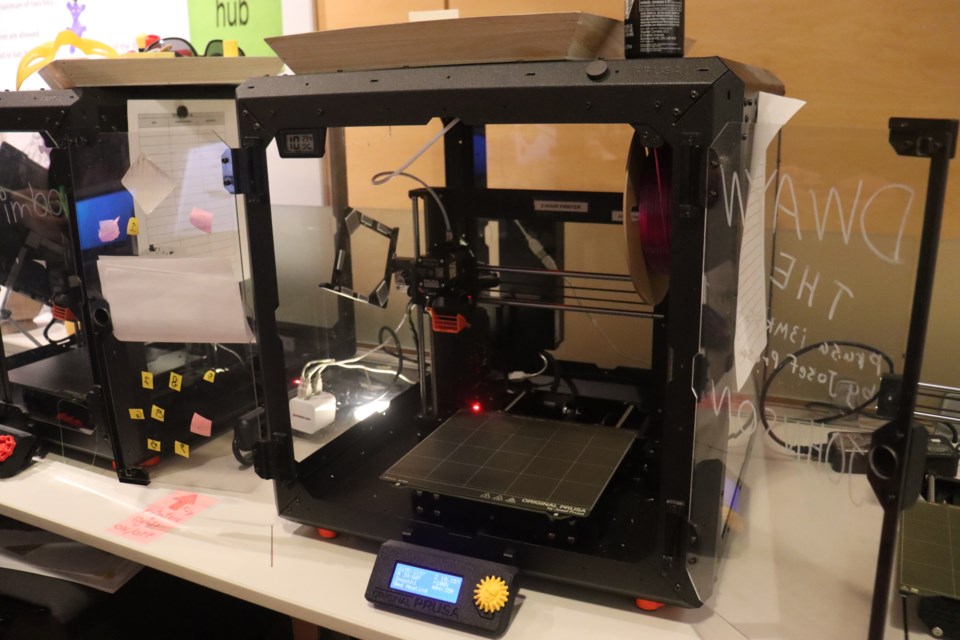

Between the library’s two printers, Heartosaur was created using the larger of the two machines since the procedure would take longer than two hours. The team also has a mini printer, which is used for smaller, less-detailed projects that take two hours or less to complete.

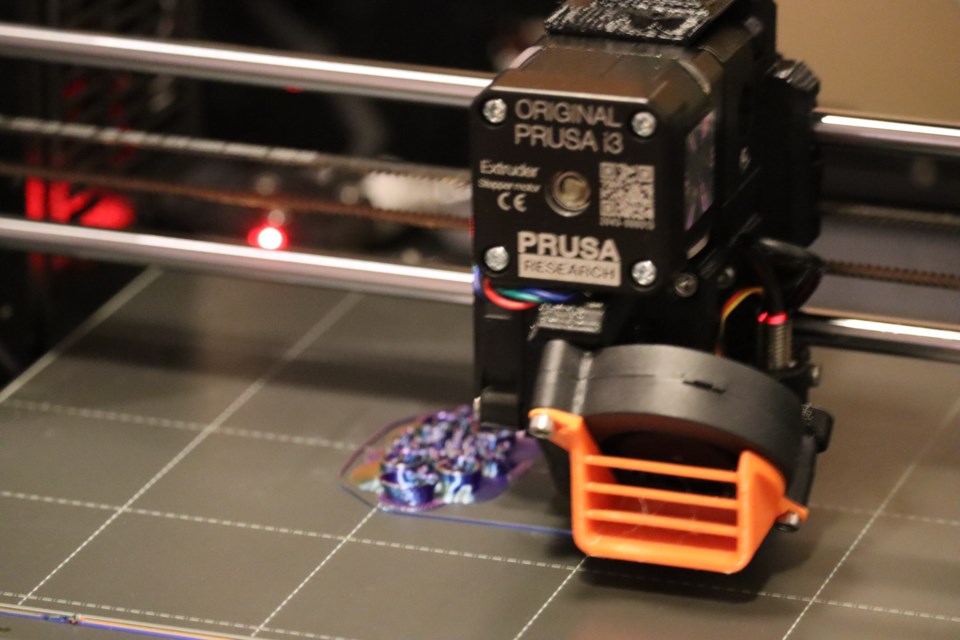

Once the Heartosaur file was transferred over to the printer, Sztainbok loaded up the machine with the multi-coloured plastic filament that I selected. The printer then began to heat up in preparation for the plastic to be melted and fed through the nozzle.

When the machine reached the appropriate temperature several minutes later, the printing process began — one layer at a time. The printing starts from the bottom of the design and works its way to the top.

“The first layer is always printed a bit thicker and much slower than the others so that it makes certain that it adheres,” Sztainbok explained. “Once it gets past the first layer, you’ll notice it will speed up a little bit. The smaller printer has a much more noticeable acceleration.”

About two and a half hours later, both dinosaurs were printed to the exact specifications I had asked for. After Sztainbok snipped off the support beams, the two dinosaurs formed the perfect heart, and the project was complete.

Now I just need to gift someone with Heartosaur. I don’t think the library’s 3D printer has the capability to create a romantic partner, so I’ll need to find a Valentine the old-fashioned way I suppose.

Torontonians love 3D printing

According to Aleksandra Majka, the senior services specialist of innovation at the Toronto Public Library, more than 6,000 visits for 3D printing were recorded across their local network of 10 hubs in 2024. Two more hubs are on the way this year.

While each of the TPL’s innovation hubs have slight operational differences from one to the next, they all have 3D printing capabilities.

“That’s our standard service, and probably one of our most popular ones,” Majka said. “Makers, tinkerers — people really do flood here, and it’s continuing to expand. People are excited about this space, and it’s outside of the traditional library idea.”

“But a lot of people still don’t realize the libraries have 3D printers,” she added. “It’s come a long way in 10 years. We’ve upgraded our models and extended our services to accommodate everyone.”

As part of her role, Majka explores new innovations and evaluates what other libraries around the world are using to promote education. If applicable, she’ll help oversee the process to implement that service into Toronto’s innovation hubs.

In addition to 3D printing at the Toronto Reference Library, their innovation hub includes virtual reality opportunities, a recording studio with a green screen and computers decked out with Adobe Creative Cloud programs for up-to-date editing and software use.

“Whatever people are looking for, we really try to provide that access,” she said. “The library is a resource for people to come in and use something that maybe they can’t afford or can’t get access to.”

“We have digital design technicians with a variety of backgrounds that can help customers create a flyer, work on their video project or use programs to create a book,” she added.

You can print that?

It might sound cliché, but the possibilities for 3D printing really are endless.

For the better part of the decade, Majka said she’s been blown away by the public’s creativity when it comes to their design and execution process.

Board game pieces, miniature figurines, prosthetics, part replacements, student projects and countless other miscellaneous items have been produced by their printers over the years.

Majka said some prints are professional based, like a local surgeon who comes in to make 3D copies of his patients’ bones to identify the correct way to drill into the bone and repair it.

Then there are more heartfelt stories, like a Downsview resident who printed a little cart so their hamster, which doesn’t have the use of its legs, could get around on its own.

Torontonians may also remember when the library was in the headlines during COVID-19 when hospitals borrowed their 3D printers so they could make more face shields and personal protective equipment.

“These are the stories we hear on a regular basis, and it genuinely makes us feel fantastic,” Majka said.

While the options are infinite, the library does have strict rules on what users are not allowed to print. Library cardholders cannot print something that can be used as a weapon, or a modification to a weapon. Sexually explicit items are also prohibited.

“Our staff are really good at identifying these things,” she said.

Majka noted that if customers aren’t satisfied with their final print, the library will offer to reprint the item at no additional charge.

“As long as they take it and they’re happy with it, we give them their receipt,” she said. “We always work with the customers and want to make sure they’re happy with the product.”