Ahead of Donald Trump’s return to the White House next week, the president-elect has his eye on Canada. Among his musings is a desire to annex the country to the United States.

Toronto is not unfamiliar with attempted American takeovers, having been a battleground during the War of 1812. At the time, the city was known as the Town of York.

That invasion is known as the Battle of York, which was fought along the shoreline of Lake Ontario, including on the modern day Exhibition Place grounds.

Local militias and British forces couldn’t hold off the invaders, leading to days of mayhem and looting, the burning of the city’s Parliament Buildings and a giant fireball explosion at Fort York.

What was the War of 1812?

The War of 1812 was the culmination of brewing tensions between Great Britain and the United States amid the Napoleonic Wars that were waged in Europe during the early 19th century.

Though the Americans were neutral in the Napoleonic Wars, the British were interfering with U.S. ships, including by blocking their access to European ports and attempting to force American sailors into British service.

As disputes over maritime rights intensified, American leaders considered their options.

Among their ideas was an invasion of the British-owned Canadian colonies, primarily Upper Canada, where some American officials believed they would receive a warm greeting.

Taking over the colonies would avenge the economic problems caused by British shipping blockades and hinder British support for Indigenous Peoples who resisted the westward expansion of the United States.

On June 12, 1812, President James Madison signed a declaration of war.

The invasion plan

By the beginning of 1813, American Major-General Henry Dearborn determined that York should be attacked.

He viewed the town as an easy target that could shift the balance of naval power on Lake Ontario to the Americans.

Dearborn believed he could seize York, then conquer the Niagara area before sending his forces to invade Kingston and Montreal.

After a delay due to high winds, 14 vessels sailed out of Sackets Harbor in New York on April 25, 1813.

The next morning, British sentries posted along the Scarborough Bluffs noticed the fleet approaching from the southeast. Using signal guns and various objects strung on a flagpole, they sent a warning down to York.

Once the fleet was sighted, British military officials began planning their defence strategy.

Major-General Roger Hale Sheaffe wanted to implement a plan similar to that used in Niagara the previous November: no opposition until the enemy was in firing range, retreat if battle didn’t go well and destroy any ammunition, provisions, or anything else that would help the Americans if it fell into their hands.

Sheaffe ordered a group of up to 100 Indigenous warriors to meet the landing party, while other soldiers were directed to stand guard at Lot Street (present-day Queen Street) by Garrison Creek.

Grenadiers were sent to the ruins of Fort Rouillé (present-day Exhibition Place), while Sheaffe waited for the militia to show up at Fort York. Estimates of the size of the British force ranged from 500 to 1,100.

Around 7 a.m. on April 27, waves of American troops rowed to shore.

The battle

Having been blown slightly off course, the Americans landed near Lake Shore Boulevard and the Dowling Avenue bridge (near present-day Sunnyside Beach).

Between 1,800 and 2,600 Americans made their way to Fort Rouillé and ran into British forces. The outnumbered Indigenous warriors were pushed back into the woods.

Steady firing on land and from schooners anchored in the lake lasted until the British retreated around 8 a.m.

Two hours later, a mobile gunpowder magazine was accidentally set off at the Western Battery (near the present-day Princes’ Gates), knocking over a gun and killing or wounding 30 troops.

American forces continued to head toward Fort York.

By 1 p.m., Sheaffe’s troops withdrew to Elmsley House at King and Graves (now Simcoe) streets, with many of the militia members deserting.

Over at Fort York, the remaining British forces ignited an ammunition stockpile as the Americans encroached.

This produced a fireball explosion that sent rocks and timber flying and could be heard at forts along the Niagara River. Around 39 American troops were killed and 224 wounded. Brigadier-General Zebulon Pike, who was commanding the U.S. forces, was among the casualties.

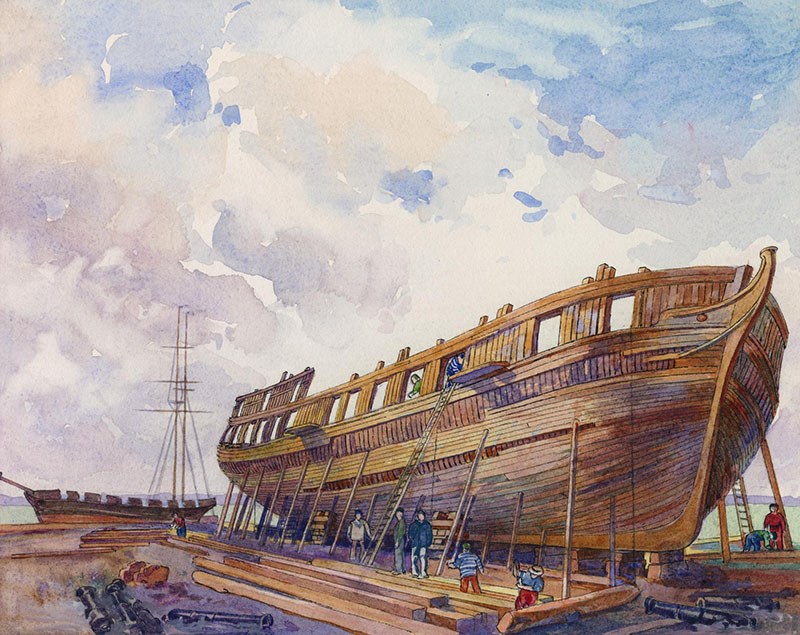

The invaders were not amused when they noticed smoke rising from York’s dockyards, where Sheaffe had ordered the torching of the HMS Sir Isaac Brock, an under-construction ship, to prevent its capture.

Nonetheless, the British were on the retreat, with Sheaffe marching his remaining troops to Kingston. Local officials negotiated capitulation terms with the Americans.

Just after 11 a.m. on April 28, 1813, the surrender was ratified and York was placed under American control.

The mayhem

Under the terms of the surrender, private property was to be respected, militia members were to be paroled and the local government would be allowed to continue its duties.

However, Dearborn showed little interest in controlling his troops.

Soon, the Americans and some locals began looting York. Homes were cleared of items ranging from clothes to cutlery. The library was pillaged and the town printing press was destroyed.

Prisoners released from their jail cells added to the mayhem.

The rampage climaxed with the burning of the Parliament Buildings, located at present-day Front and Parliament Streets, during the early morning of April 30, 1813.

Rumours had spread among the Americans that a human scalp was on display inside the buildings. Allegedly, one was found hanging above the ceremonial mace by the speaker’s chair and was later presented to Dearborn.

While many believed the Americans set the Parliament Buildings on fire, one British officer claimed local looters were actually responsible.

What is certain is that the mace was taken away by American troops.

It was kept at the United States Naval Academy Museum in Annapolis, Md., until President Franklin Delano Roosevelt returned it in 1934 to signify friendship between Canadians and Americans. Today it is displayed at Queen’s Park.

The Americans departed for Niagara on May 8. A planned attack on Fort George, near modern day St. Catherines, was delayed when troops fell ill with diarrhea and dysentery, and sailed back to Sackets Harbor.

The blowback

Following the failed defence of York, Sheaffe was soon relieved of his duties.

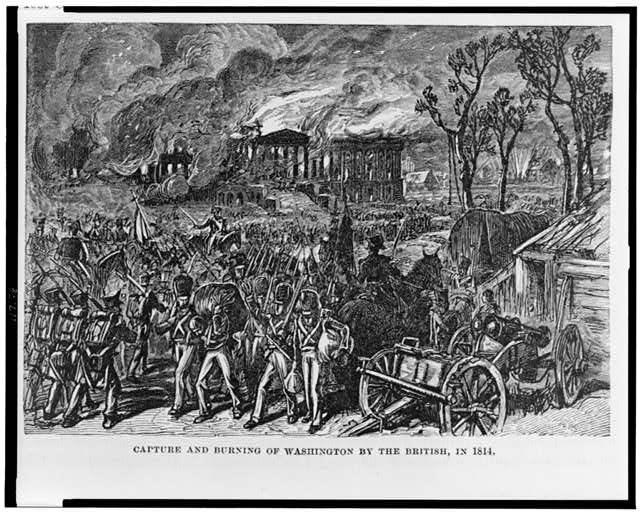

The British got revenge for the burning of the Parliament Buildings and other damage inflicted on their settlements when they attacked Washington, D.C. the following year.

In August 1814, they set the White House on fire.

The war ended when the United States ratified the Treaty of Ghent in February 1815, which restored the prewar boundary between the Americans and the British colonies.

There are numerous memorials, plaques and pieces of public art around the City of Toronto commemorating the War of 1812 and the Battle of York, including The Old Soldier sculpture in Victoria Memorial Square.

Douglas Coupland’s Monument to the War of 1812, also called Toy Soldiers, at Bathurst Street and Lake Shore Boulevard offers a more whimsical interpretation.

The Parliament Buildings were rebuilt by 1820 but were destroyed by another fire four years later. The site — which was later home to a courthouse, jail, then car dealership — has had extensive archaeological work done and will be adjacent to the Ontario Line’s Corktown station.

Who actually won the War of 1812 will be an eternal debate — one that will be reawakened if the next U.S. administration goes beyond dreaming of adding Canada to its territory.

_____

Sources: Historic Fort York 1793-1993 by Carl Benn (Toronto: Natural Heritage/Natural History, 1993) and Capital in Flames by Robert Malcolmson (Montreal: Robin Brass Studio, 2008).

Jamie Bradburn is a Toronto-based freelance writer and historian, specializing in tales of the city and beyond. His work has been published by Spacing, the Toronto Star and TVO.